Our son Neil is 14. He was diagnosed at a week old with cystic fibrosis. When he couldn’t hold up his head or sit at age one he was diagnosed with cerebral palsy and developmental delays. He didn’t walk on his own till he was 11—that was an amazing day.

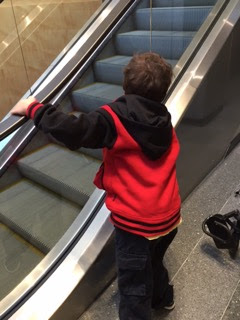

It’s fair to say that Neil’s three favourite places are: a swimming pool, where he can engage in Olympic-calibre, slap-splashing; a set of stairs—any set of stairs, any size, any height, carpeted or not, anywhere, including those in buildings at Drexel University in Philadelphia, where I’m on the faculty—and the escalators at a local bookstore.

From the start of Neil’s fascination with the bookstore escalators, the staff has been kind and accommodating. My wife Sheila and I know many by name. Some days it’s almost like a scene from the classic television show Cheers, when Norm Petersen trundled in to the fictional Boston bar to enthusiastic shouts of “Norm!” Other kids have been castigated for their rambunctious escalator behaviour, but Neil rolls merrily on, up and down, laughing.

Once, when one of the escalators was shut down for repairs, a genuine look of sadness crossed the face of Tom, who like many of his colleagues has come to know what these visits mean to Neil. We improvised, of course; the malfunctioning escalator became a set of stairs. We cruised up and stepped down.

But while the store’s employees have been kind—so much so that Sheila and I sent a letter thanking them to the corporate office—it’s the range of public reactions to Neil, and his intellectual disability, that coalesced into the leaping-off point for my next book.

With apologies to the very talented people who created the hit movie Inside Out, when we go out with Neil the looks we get typically reflect:

Disgust, as if the person is thinking—but will never muster the guts to say—“how could these people bring him here?” Some sneer visibly at Neil. Some change direction to avoid any contact with him. Some act as though they might catch his challenges. Others grumble when he cuts, with no malicious intent, in front of them to get on the escalator.

Indifference is the look we most frequently experience, as if Neil isn’t even there. Maybe intentional indifference is more accurate; these folks see him, they just don’t “see” him. To be fair, it may be that they’re wrapped up in what’s taking place in their own lives—getting a book for school, for example, or trying to quiet a grouchy child.

Curiosity It’s as though they’ve come upon an animal seen only in the wild or are gawking at a museum exhibit. Kids most often display this look, although to be fair, it probably originates in a lack of exposure to folks like Neil. It’s actually a mix of wonder and…

Fear—Neil doesn’t notice it, thankfully. But Sheila and I have been brought to tears more than once by kids who cringe when they see him, as though they’ve seen a monster, and duck behind a nearby parent.

Happiness It’s heartwarming when folks express gratitude to Neil for purportedly keeping the escalator moving. “Are you helping us get to the top?” they’ll ask. “Thanks a lot buddy,” we hear now and then. Others just smile at him: some out of a sense of obligation, others to check off “was nice to a disabled person,” and still others just because they recognize that he’s a very compelling individual.

A couple of weeks before Christmas last year, a middle-aged couple who watched Neil for about an hour from a table in the café stopped us between descent and ascent and handed us a $25 gift card. They told us he was a beautiful young man—quite true—and asked that we use the card to buy him a present.

Finally, we have Emulation. Neil has inspired a small but dedicated legion of imitators, kids who watch the escalator, grasp and pretend to propel the handrails, and now and then follow us on our forays.

During a visit this past October, two young girls, probably 12 or 13, hitched about a 10-minute ride one step behind us. Others dip into the escalator shenanigans songbook, sitting on the steps, running up and down, and attempting the time-honoured “go down the up” and its just-as-exciting cousin, “go up the down.” Sheila and I cringe with fear and a little embarrassment when a kid gets in trouble with a parent or a staff member for wanting to hang out and ride.

I’d guess that for all of these folks—the nasty, the encouraging, even the kind—Neil’s presence at the foot of the escalator is unusual and unexpected. We’ve learned that families like ours, with a child with an intellectual disability, are often reluctant to go out in public.

My new book will dissect how the news media portray people with intellectual disabilities—as hopeless victims or spunky competitors who sink a basket after sitting on the bench all season. Rarely do we see people with intellectual disabilities celebrated for who they are as individuals.

A huge part of the book will be stories from families with experiences like ours. I’ve put together an open-ended survey to collect stories from parents about how their child is treated by the general public and family, and how this influences their lives. If you’re the parent of a child with an intellectual disability, please consider filling out this anonymous survey. Thank you in advance for your help!

Ron Bishop is a professor in the Department of Communication at Drexel University in Philadelphia. To speak with him about his upcoming book Holding Up The Sky Together, e-mail Ron at rcbsam@comcast.net.

1 comments:

What a great book project! I'll make sure I fill out your survey - thank you for the opportunity to add other family voices.

I used to coordinate a peer support program for families who had a baby with a new diagnosis of Down syndrome. One of our most common questions was: will people stare at us in the mall? I used to always say: yes, some people will. Other people are too busy to even notice you. Others do express the disgust or fear you talk about. But there is a certain percentage that smile a knowing smile, engage with my son in some way - those are the ones I told families to remember. These are the folks that matter.

But thank you for deeply exploring this super important question.

Post a Comment