Her title is therapeutic clown, but she says “therapeutic clown practitioner” is more fitting. “Dr. Flap is the therapeutic clown,” she says. “The practitioner is the clinician under the nose.” Helen came to Holland Bloorview in 2007 to join Ricky, the clown we knew as Jamie Burnett, who has since died.

This is how I described the pair in 2012: “No matter which room they were in, or whether the child could speak or move, the duo would create a kind of magic that bounced like a ball between the clowns and the child and the child and the clowns. Sometimes the magic moved back and forth through the blinks of the eyes alone, sometimes through silly body movements and sounds. Sometimes it was a child conducting the taps of drum brushes on a wheelchair tray or commanding the clowns to perform outlandish antics. Sometimes it was an elaborate story the child told and the clowns acted out. Other times it was a dance to the strums of a red ukulele.”

In 2010, researchers here published a study that showed that even children who can’t move or communicate verbally respond to our therapeutic clowns with changes in skin temperature, sweat level and heart and breathing rate.

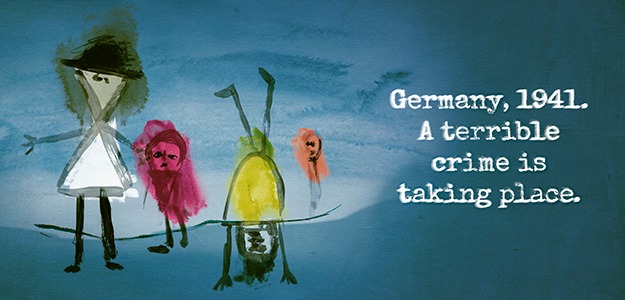

BLOOM interviewed Helen as she was about to do a 24 Hour Uke-A-Thon to raise funds for our therapeutic clown program, which is completely funded through donations. In the photo above she appears with Manuel Rodriguez, who is Nurse Polo.

BLOOM: What led you into this field?

Helen Donnelly: I was a clown with Cirque de Soleil and was building my own shows in theatres. A colleague of mine at SickKids encouraged me to audition for a position there, but I resisted. I kept thinking there’s no way I could handle the sadness and the grief. How do you clown through grief and how could I possibly find my joy in a place where people are anxious and fatigued and in pain? I didn’t think I could handle it.

Two years later another position came up and this time I found myself intrigued and not saying no. I auditioned in the atrium at SickKids and my heart just leapt and I said ‘This is what I’m built to do as well.’ The similarities between circus and theatre as a clown, and being in a health care setting as a clown, all came together.

BLOOM: How did you end up at Holland Bloorview?

Helen Donnelly: My experience at SickKids was fruitful in that I learned an awful lot about how to clown in the medical world. But the structure of being a clown working solo was very challenging. I found working alone on a unit was emotionally and physically fatiguing and there wasn’t the kind of rigorous artistic support that I was used to. Then Jamie contacted me from Holland Bloorview and said he was looking for a partner. He wanted to mirror global best practices of having the duo model of clown in hospital.

BLOOM: What are the benefits of two clowns working together?

Helen Donnelly: Having worked both ways, there are so many benefits to the duo. There's the emotional support. And having a partner who can constantly witness and feed back about the work ensures a greater degree of safety for clients and high artistic standards.

Working in a duo is inherently more ‘artistic’ in nature. It sets us up to be partners, rivals, teacher-student, or both ‘in trouble,’ according to the child’s imagination. Having two clowns means many more choices for the clients. And kids are smart and instinctively know what to do with two contrasting 'fools!'

You can imagine if you’re a 17-year-old who is resentful, refusing therapies and fighting depression, the last thing you want is a single clown knocking on your door, asking permission to come in.

We feel a better way is to have two clowns having a 'heated argument,' let's say, just outside the door, and to have one of the clowns turn to the client and say ‘Excuse me, do you mind? We’re in the middle of something here, so this is none of your beeswax anyway.’ You’re trying to assess if there’s a crack there—a way in to something this teen might delight in.

Not all clients want to be interacting one-on-one, or at all. When you have two clowns you have so many more options. You can have one clown side with the child against the other clown. Or have the child be our boss and tell us what to do. Or you can have the child and two clowns playfully correct the parent or clinician. With the duo clown model we offer that choice of collaborating or being a passive observer.

BLOOM: What's a typical day like now?

Helen Donnelly: I work three days a week with Suzette Araujo, who is Nurse Flutter. Manuel Rodriguez, who is Nurse Polo, comes in if one of us is absent.

We check in, and we might go to inter-professional rounds or meet with child life specialists, in addition to looking up all of the clients we’re about to see on the electronic medical record. That helps us prioritize our client list. We spend one day a week on each unit from about 1:30 to 5 p.m.

BLOOM: What do you do?

Helen Donnelly: There are three main purposes. One is to seek out opportunities for kids and youth to feel powerful. It could be a baby who makes eye contact with us and we see him as our lawyer—which might tickle the parent, because we’re elevating the status of this baby high above us. We seek opportunities for youth to manipulate us in any way they wish—to outsmart us or to correct us.

BLOOM: Why is it important for kids to feel powerful in hospital?

Helen Donnelly: Clients feel a lot of their choices are taken from them. They’re missing a lot of the pieces that define who they are. We want them to feel most authentically like themselves again, and to be in control again.

BLOOM: What are the other purposes?

Helen Donnelly: The second is to collaborate with our fellow clinicians during a medical procedure or during therapy sessions.

BLOOM: Why is that helpful?

Helen Donnelly: The procedure may be frightening or painful and we have diversion techniques we can adopt, where we see immediate results.

BLOOM: Can you give an example?

Helen Donnelly: If there’s a wound change, which can take quite a while, we might employ physical comedy. We might get stuck inside the child’s bathroom and can’t find our way out, so we’re pleading at the door for the child to help us get out. Or maybe the kid, with a wave of an arm, can freeze us and we’re frozen, and then they can wave again and we’re brought back to life. It’s like visual candy, and it’s all housed in a comedic framework which can take us to some wonderfully dark places. It’s not always about frivolity.

There can be a lot of therapeutic merit in getting youth to release some of the darker feelings they might have. Because we’re artists, we have many skills in our back-pocket. We can make a rock opera out of their feelings. We’re musical by nature, and we’re skilled in the art of improvisation. We're flexible and can go where they want to lead us, fearlessly and with joy.

The great thing about clowns is we’re playful rule-breakers, we’re not beholden to society’s norms. Kids and teens instinctively understand what that looks like and how to use their clowns. It’s only when we become adults that we forget.

BLOOM: What is the other purpose?

Helen Donnelly: A philosophical aim is to seek out ways to change the atmosphere of the entire unit. So, how can we lift the spirits of our fellow clinicians and give them the kind of encouragement and praise that they always deserve? We may make up songs for clinicians. ‘Hang in there’ seems to be quite popular these days.

I’ve been criticized by a few therapeutic clown programs around the world for spending what they perceive is too much time on our clinicians. That’s baffling when you consider that you can make a difference within one minute. Good care trickles down, and if you look after the caregivers, it benefits everyone. They are the unsung heroes here and, as servants, our job is to highlight where those heroes are.

A very important part of our day is when we debrief and reflect on the interventions at the end of the day. We pick apart what worked, what didn’t and why, and come up with a plan for next time.

The remaining half hour is documentation. We’re the only clowns in the world to electronically document every intervention in the permanent health care records of our clients. Lots of clowns document, but not electronically. The benefit is that clinicians can check in on our notes: ‘Oh, does Johnny like clowns? Oh, wow, it says he’s musical.’ So they’re learning aspects about their clients that they can use.

BLOOM: Who is Dr. Flap?

Helen Donnelly: Dr. Flap is a flight doctor from the fictitious island of Tubegosh, which is in the Atlantic, Pacific, Mediterranean area.

BLOOM: That’s a lot to wrap your head around.

Helen Donnelly: Ha! Oh, and Dr. Flap is regularly regarded as genderless, so often goes by the pronoun ‘they’ or ‘their.’

BLOOM: Why is that important?

Helen Donnelly: There’s a tradition among some indigenous cultures in which the fool in that society is gender-fluid. This is something that always appealed to me when it comes to offering choices to our audience. I can’t tell you how much joy we get every time a client decides Dr. Flap is male—and what a wonderful thing it is when the parent does not correct their child! In this way, clown can symbolize fluidity in many things—that moods can change, a person’s health can change, our gender can change. Anything is possible.

BLOOM: Cool. What happens inside you when you put on your costume?

Helen Donnelly: We like to call them clown outfits or clown skins, because the clown is a huge aspect of our authentic self. When the nose goes on, for me, it’s a transformation through Helen, and up and out into a freer version of myself. I’m not losing anything I am. I’m not denying my own function or moods, but I’m giving myself freedom to express them in a much more artistic fashion.

Dr. Flap is a better or bigger version of Helen. This transformation inherently gives the clown artist a lot of energy and resiliency. As Helen, I am devastated to learn about some of the things that occur in this hospital. But as Dr. Flap, I’ve been able to withstand so much hardship and witness so much pain.

There’s something about the nose that keeps you focused on what’s really going on, and what you perceive is needed in the moment. It’s the least selfish you can ever be. It’s truly putting yourself in that 'servant’s heart' frame of mind. It frees you up from being in your head or in your worries. You find a lightness. It’s because you’re giving yourself permission to be in this lighter self that you can hone in on what’s needed in the moment.

BLOOM: What do you love about the work?

Helen Donnelly: It’s the opportunity to offer my art and all that I am in a system that I love, and one that is totally different than the one I perform in otherwise. I’ve always been around healthcare and I’m comfortable here. I was a kid in health care myself, and I was a candy striper in the ‘80s.

BLOOM: You were a patient?

Helen Donnelly: I was bitten by a dog when I was five and I had to have several surgeries to reconstruct my cheek.

BLOOM: I didn’t know you had that experience. What was it like for you in hospital?

Helen Donnelly: It was amazing. I remember my doctor’s name and my roommate was 16. She was there for an appendix operation. There was a big doll house in our room and she and I would play doll house for hours. I got presents from my parents and friends.

BLOOM: Was the surgery painful?

Helen Donnelly: I don’t remember the pain from there. What I do remember is the aftermath—the reintegration back into school.

BLOOM: How long were you hospitalized?

Helen Donnelly: I think it was a couple of weeks, and I had several surgeries over several years. But the emotional pain was so much worse. It took me a long time to heal, and I had to constantly wear bandages and put on special cream. Kids aren’t the most delicate of beings. So I was called a monster and I was the kid in the playground you’d feel sorry for—the one holding the teacher’s hand at recess because no one wanted to play with me.

BLOOM: Was this at the beginning of kindergarten?

Helen Donnelly: Yes. My socialization was halted for a long time. I found it difficult to connect with people and make friends. Everyone stayed away from me. On the good side, I had a remarkably imaginative life and we lived rurally, in the country. So it was natural that I would connect to the fairies in the forest, and build whole worlds, and become different entities. And that’s what led me to theatre.

BLOOM: You were talking about what you loved about working here.

Helen Donnelly: It’s the opportunity to have my dreams realized, and to carry on Jamie’s legacy. That is a huge motivator for getting out of bed every day. When Jamie was declining, I promised him that I would continue to do two things: the first was to ensure that our program is secure and safe, and the second was to build a school for therapeutic clown. I feel so fortunate to have arrived at Holland Bloorview, in a place that wants those two things to happen just as strongly as I do.

BLOOM: What is the certification?

Helen Donnelly: I’m building a certification for therapeutic clown that will be the first of its kind in North America. I’m building it through George Brown College, in partnership with Holland Bloorview. We need to have formalized training with proper supervision and evaluation.

BLOOM: Amazing! If you could change one thing in health care, what would it be?

Helen Donnelly: Time constraints. I’d love it if there were five of me.

Also, part of the biggest joy I have is finding a partner who deeply contrasts with me. But that can also be a challenge at times.

BLOOM: Why do the clowns need to be so different?

Helen Donnelly: Contrast is the essence of comedy. It’s just not true that you can have two similar clowns that can bring about the kind of comedic effect that two very opposite personas can. Because my clown partners contrast so deeply with me, it only makes sense that as humans we would have less in common with each other. So, you might get a type A personality, like me, working with co-horts who are type B personalities. That can be a challenge for all of us at times. I often secretly feel sorry for my partners!

BLOOM: Because you are such different people. How do you manage the emotions that come with the job?

Helen Donnelly: We take self-care extremely seriously. We’re the kidney of the hospital: filtering everyone else’s emotions, as well as our own, is the art of the clown. One of the benefits of the duo-ship is we dedicate time to sharing our feelings with each other. You have someone right there who’s witnessed the work. At the end of the day, we share how it felt and what we need from each other.

We make sure to give ourselves a break if we’ve had a difficult intervention. Six times a year, outside of clown hours, we meet with a psychotherapist for two-and-a-half hours of dedicated time, to talk about the effect of all of the filtering we do. We have to be healthy, happy, centred and grounded

BLOOM: Do you have advice for other clinicians about the emotional side of the work?

Helen Donnelly: What’s helpful for me is to do practical things to help me refocus on where I’m needed most. It may be as simple as saying ‘I’m feeling this way, but that’s just a feeling in the moment.’ Then I look at how I can be a servant in this time, instead of worrying about how it’s affecting me.

But we never deny what we’re feeling. Clowns are the ones that can name the elephant in the room and get away with it. Other clinicians may find this helpful, too.

Instead of deflecting or diverting from what’s happening, it may be interesting to name it—express that you’ve noticed that something is going on with your client. Chances are, they want to express it, and are trying to find a way to tell you. We can all help them by agreeing that something is being felt, and something is being 'tasted' in the room.

If a client shares something that is absolutely sad or tragic, for us it would be disrespectful and untruthful to not let that affect us authentically. It’s important to them to see the effect of their news on their clowns. It builds trust, and we need to feel what they’re going through, to serve them well.

We’re not afraid of emotions and we need to express all of it to be the most human we can be. Ironically, through the filter and the mystery of the clown—this masked being— we’re able to find the most truthful way of being.

BLOOM: It reminds me of a narrative nursing group we did here, where the stories that staff shared unmasked their vulnerability, and how freeing that was.

Helen Donnelly: A good clown is a mask that reveals, and instinctively, everyone knows that. If you’re truly willing to reveal yourself, it gives others permission to reveal themselves, to share where we’re at, what we’re feeling and what’s important.

BLOOM: How long did you work with Ricky?

Helen Donnelly: Just over three years.

BLOOM: He was so loved here. How did you carry on after he became sick and died?

Helen Donnelly: It was the hardest thing I’ve ever had to go through. I did take some time off, and when I came back, I allowed myself lots and lots of breaks. My big hope was to find a way to balance the joy of being back with the grief that I was still carrying, and I have to say that the clinicians and clients got me through it. I could tell you so many stories about how clients wouldn’t let me off the hook about my grief, and they did it in such great, creative ways.

BLOOM: You mentioned that some of the families had asked that you not disclose to their child that Jamie had died.

Helen Donnelly: Yes. That was an almost impossible situation. Sometimes one child in the room could be told, and another couldn’t.

BLOOM: I guess the thought was that it was family-centred to allow parents to make that choice? But on the other hand, it seems to somehow minimize or erase what happened.

Helen Donnelly: I think the system can afford to really examine how we grieve here, and how we celebrate the memories of people who died here.

BLOOM: So how did you respond to children who couldn’t know the truth?

Helen Donnelly: I had to be really creative, while still honouring what my truth was. So often if it was a client who really wanted to know, but I wasn’t permitted to tell them, I might say: ‘I’ve been looking for him, too. I miss him too. Tell me what you miss about him.’ And then we’d talk about him and honour him and honour what we miss the most.

I knew going through this whole ordeal that it was inevitable that I needed to find a new clown partner, and I found the perfect partner in Manuel. He was like a bright light streaking across the universe. The type of joy that is central to his being was exactly what I needed. He is my rock. He was so different from Ricky, yet that lightness and innocence was so similar. Manuel was able to fill those big shoes with such grace and an immense sense of openness and willingness, and people picked up on it. I leaned heavily on it.

BLOOM: You work with many children who are non-verbal and have very complex disabilities. What have you learned from them?

Helen Donnelly: The joy of connecting with them and meeting them where they’re at, and the joy of investigating inventive new ways to elicit a collaboration or a communication. I believe that our observational skills have skyrocketed because of them.

Engaging with kids who communicate in alternative ways inherently demands a sensitivity and inventive approach that you otherwise wouldn’t adopt. It’s a much richer experience, and the techniques we adopt with the more complex kids are ones we use with verbal kids all the time. Things like mirroring or use of mime or contrasting pitch.

BLOOM: So does working with children who can’t communicate conventionally allow you to hone these skills?

Helen Donnelly: It’s almost like specialized training. I’m a better clown because of it.

BLOOM: Have your thoughts about disability changed since you first came here?

Helen Donnelly: When I first came, like a lot of people who happen to be able-bodied, I couldn’t help but feel emotions like pity and sadness, and sometimes frustration. I’m not saying those things have been completely wiped out—that’s not true. I’m saying that I’ve grown to really appreciate how capable kids are of expressing their needs and moods and how much joy there is to be had just sharing our time together.

Seeing how these children’s lives are being celebrated by everyone—not just by the parents or the clowns, but by all clinicians—and seeing the affect they have on everyone, it gives you hope that society can learn from how they live their days and what they choose to do.

BLOOM: Do you mean that in seeing how people’s ways of thinking change inside these walls, that perhaps we can expect similar social change outside?

Helen Donnelly: We’re a kinder society in here. But the winds are changing and shifting and that gives me hope.